The U.S Army's Security Force Assistance Triad: Security Force Assistance Brigades, Special Forces and the State Partnership Program

The U.S Army's Security Force Assistance Triad: Security Force Assistance Brigades, Special Forces and the State Partnership Program

by Charles McEnany

Spotlight 22-3, October 2022

As the Army modernizes for MDO—competing with or defeating adversaries who threaten the United States in the land, sea, air, space and cyberspace—observers might be perplexed by the Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs). Given the future battlefield, it appears counterintuitive that the Army would make security force assistance (SFA)—“activities that support the development of the capacity and capability of foreign security forces and their supporting institutions”1—central to its modernization.

The Army’s SFA is integral to strategic competition. With global threats and aggressive attempts by China and Russia to rebalance the international order, the Army has calculated that building partner capability is critical for competing.

Though the SFABs are the first purpose-built formation for SFA, the Army has conducted these missions for decades, often utilizing Army Special Forces (SF) Green Berets and the National Guard State Partnership Program (SPP). Through the three complementary legs of the SFA triad—SFABs, SF and SPP—the Army maintains a cost-effective and regionally tailored capability to train foreign forces while fostering broader governmental and societal engagement.

The Strategic Environment

The United States and its allies face a volatile security landscape. Though China poses the most comprehensive challenge, Russia’s war in Ukraine is a reminder that the United States cannot dictate the demands on its foreign policy. The same principle applies to other security flashpoints, namely North Korea, Iran, international terrorism, climate change and pandemics.

Persistent and aggressive strategic competition is already occurring as China and Russia attempt to shape the international order. Competition is neither peace nor conflict, as competitors leverage all instruments of national power—including political, military, economic, diplomatic, technological and informational—to achieve their aims. Though Beijing and Moscow hope to achieve their aims without military confrontation with the United States, they intend to prevail, should it occur. As a result, they have pursued military modernization while acting below the threshold of armed conflict to weaken the United States and its allies.

Despite the severity of the international security environment, it is unlikely that the U.S. defense budget will consistently receive the 3–5 percent annual growth estimated by the 2018 National Defense Strategy Commission as necessary to keep pace with these threats.2 Prioritizing finite resources against increasingly severe and numerous global threats is a daunting challenge for the Pentagon.

These factors require that the U.S. military bolster its network of allies and partners to maximize the value of its defense resources while advancing its influence.

U.S. Army Soldiers with 5th Security Forces Assistance Brigade (SFAB) and members of the Maldives National Defense Forces pose for a group photo at Central Area Command, Kahdhoo, Maldives, 26 May 2022. SFABs train and advise foreign security forces to improve partner capabilities and facilitate achievement of U.S. strategic objectives (U.S. Army photo by Specialist Jacob Núñez).

U.S. Army Soldiers with 5th Security Forces Assistance Brigade (SFAB) and members of the Maldives National Defense Forces pose for a group photo at Central Area Command, Kahdhoo, Maldives, 26 May 2022. SFABs train and advise foreign security forces to improve partner capabilities and facilitate achievement of U.S. strategic objectives (U.S. Army photo by Specialist Jacob Núñez).

The Value of Security Force Assistance

SFA (not to be confused with SFABs, which are one formation that conducts SFA) is a broad concept, including organizing, training, equipping, rebuilding and advising foreign security forces.3 This Spotlight considers U.S. Army SFA and not the contributions of the Navy, Air Force and Marines. While Army SFA is recently associated with advising forces in Afghanistan and Iraq, strategic competition presents opportunities to assist partners with robust governments that face military shortfalls relative to a regional hegemon.

Land force SFA has unique benefits, with both tactical and strategic effects. Nearly every country maintains a land force,4 giving the Army an in-roads through its global landpower network. Even in regions thought to be naval-dominated, relationships forged by the Army can set the foundation for broader U.S. engagement. For example, two-thirds of countries in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command have chiefs of defense who are army generals.5

SFA provides the joint force with global access, influence and presence, allowing the Pentagon to set favorable conditions for conflict. Presence gives Washington a pulse on local and regional developments that often can only be fully appreciated through human relationships. This access also generates favorable positional advantages for U.S. forces that can enable joint force operations or complicate adversary attempts for horizontal escalation.

U.S. presence directly contributes to conventional deterrence. U.S. forces on the ground with foreign partners demonstrate commitment and can serve as a “tripwire.” Even a small U.S. force may deter an adversary from initiating conflict against a local country through the implication that such an initiation would draw the United States into a conflict. Additionally, U.S.-trained partner forces able to resist military coercion can deter adversaries from conflict initiation.

Defining SFA

Due to its broad nature, security force assistance (SFA) can be challenging to define. SFA is a subset of security cooperation, but it is not identical to security assistance, which refers to a group of programs authorized under Title 22 of the U.S. Code. This Spotlight applies the definition used by DoD and the Joint Center for International Security Force Assistance (JCISFA): “activities that support the development of the capacity and capability of foreign security forces and their supporting institutions.” The Army defines SFA similarly: “unified action to generate, employ and sustain local, host-nation or regional security forces in support of a legitimate authority”6 Further, SFA is often conveyed through various terms, like foreign internal defense or train, advise and assist. SFA, as discussed in this Spotlight, most closely resembles train, advise and assist.

SFA also builds integrated deterrence, summarized by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin as “using every military and non-military tool in lock-step with allies and partners.”7 Besides military-to-military engagements, SFA includes training between the U.S. military and partner domestic security services, such as law enforcement or border protection.8 This assistance builds partner resilience against vulnerabilities that adversaries exploit. As integrated deterrence incorporates non-military tools, such as economics and diplomacy, the potential for SFA to advance U.S. influence outside the military is vital. Positive engagement with the U.S. military reinforces Washington as the global partner of choice. These relationships can develop into whole-of-government and whole-of-society connections—expanding the network of nations necessary to uphold the international order.

Additionally, by empowering local forces to contribute more to their security, SFA can allow the Pentagon to execute its regional prioritization. Since U.S.-trained forces are better prepared to prevail against adversaries, the United States may be able to avoid conflict altogether. For example, U.S. training of Ukrainian forces, which has primarily been conducted by Army SF since 20149 and through Ukraine’s SPP partnership with California (and other U.S. states),10 has helped the United States to remain out of direct conflict. This training is a small investment compared to the potential costs of open war with Russia that would, among other impacts, divert U.S. resources from the Indo-Pacific. If the United States does become involved in a conflict, SFA encourages burden-sharing by integrating allies and partners into multinational operations.

SFA is also mutually beneficial for U.S. capability. Soldiers learn tactical and operational skills from their partners, who often have niche capabilities and an intimate understanding of the local culture, operational environment and regional adversaries. The Army can integrate these lessons into training and doctrine through after-action reviews, thus broadly improving U.S. forces.

The Importance of Allies and Partners

Allies and partners feature prominently in recent defense strategies. The 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) makes “Strengthen[ing] Alliances and Attract[ing] New Partners” one of three lines of effort, stating that “allies and partners provide complementary capabilities and forces along with unique perspectives, regional relationships and information that improve our understanding of the environment and expand our options.”11 Likewise, the 2022 NDS calls for incorporating “ally and partner perspectives, competencies and advantages at every stage of defense planning.”12

The Army has made SFA central to modernization. Army Chief of Staff General James McConville noted, “A strong military comes from strong relationships. . . . Together with allies and partners, we have many more options collectively than we do as individual nations to maintain our strength and readiness.”13 The Army underscored this commitment in 2017 by creating the first SFAB—one of two signature modernization formations (the Multi-Domain Task Force—MDTF—being the other).

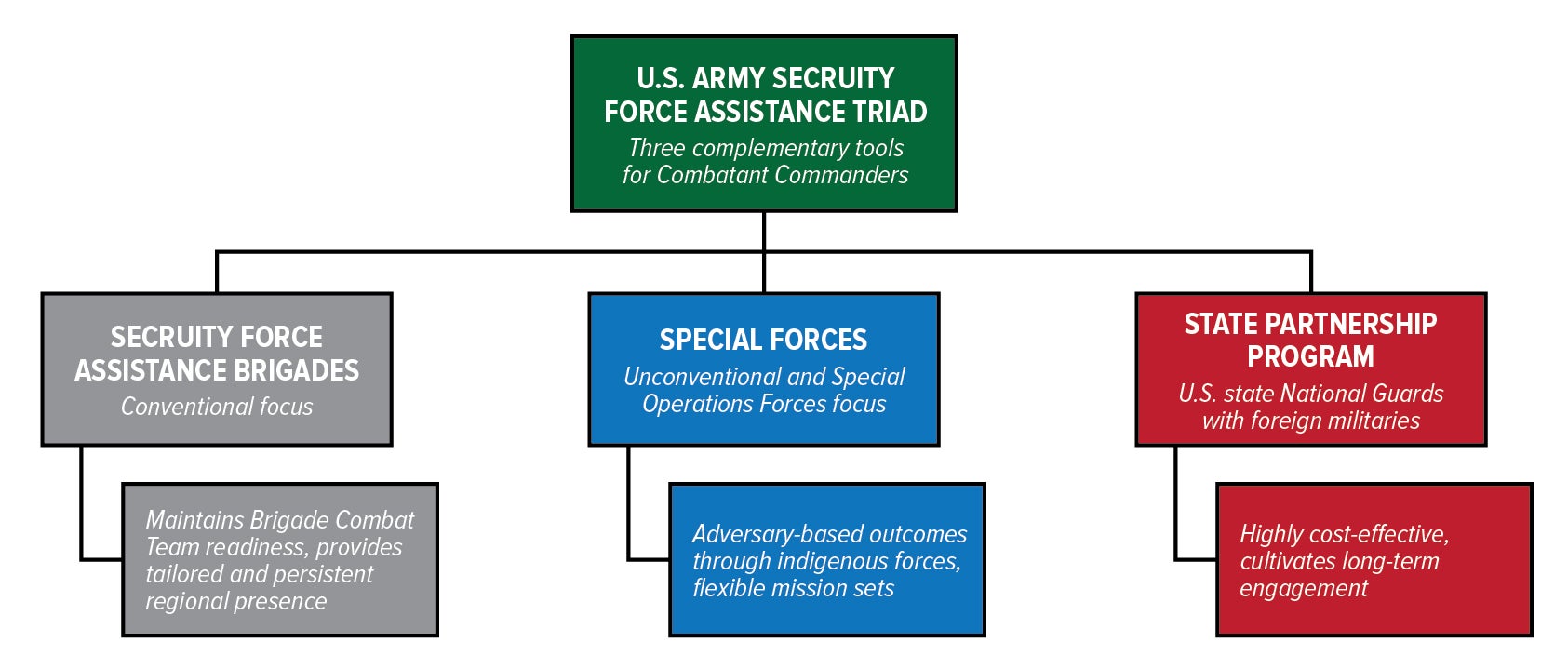

Figure 1: The Army's SFA Triad (Enlarge)

Figure 1: The Army's SFA Triad (Enlarge)

In combination, SFABs, SF and SPP form a “triad” of Army SFA (see Figure 1). Though the three legs of the triad are not necessarily the only organizations in the Army that conduct SFA, it is a central doctrinal component of each. The three formations are best perceived as different tools in the same SFA toolkit. They are complementary, un-redundant SFA capabilities for combatant commanders to utilize based on their respective strengths.

Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs)

The Army has established six SFABs—five in the active component regionally aligned to geographic combatant commands (GCCs) and one in the National Guard with a global focus. Under the Security Force Assistance Command (SFAC), which recruits, assesses, selects and prepares SFABs for global employment, these formations are key to Army MDO through their support of GCC security cooperation requirements.

SFAB Organization

Each SFAB, commanded by a colonel or brigadier general, consists of approximately 800 Soldiers, each serving a three-year assignment. The officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) must volunteer and are the SFABs’ core. Major General Scott Jackson, founding Commander of the 1st SFAB, observed, “Every good advisor is a good Soldier, but not every Soldier is a good advisor.”14

SFABs recruit experienced Soldiers (the average SFAB officer has 13 years of service, and the average NCO has ten years of service)15 who are experts in their military occupational specialty (MOS) and have previously served at the level for which SFAC recruits them.16 Candidates undergo an extensive selection process. Once accepted to the SFAB, each Soldier receives six weeks of training in advisory skills at the Military Advisor Training Academy in Fort Benning, Georgia.17 Advisors also receive regionally relevant cultural, language and foreign weapons training.18

SFABs are comprised of the capabilities needed to train a foreign conventional force. These capabilities include:

- three maneuver battalions, advising across all warfighting functions;

- a field artillery battalion, providing fire support and targeting expertise;

- an engineer battalion, providing engineering, intelligence and communications expertise; and

- a logistics battalion, providing logistics and medical expertise.

SFABs are divided into 60 multifunctional teams—Maneuver Advising Teams, Field Artillery Advising Teams, Engineer Advising Teams and Logistics Advising Teams—each of which boast four to twelve Soldiers and is headed by a captain.19

In 2021, SFAC regionally aligned the SFABs to each GCC (see Table 1) except for U.S. Northern Command. Regional alignment allows SFABs to build expertise in the operational environment, culture and languages of their respective area of responsibility (AoR) and, therefore, deeper engagement with partners. The 54th SFAB (National Guard) is not regionally aligned but it is employed globally as an enabler to support active component SFABs and GCC requirements.

Table 1: Security Force Assistance Brigades (Enlarge)

Table 1: Security Force Assistance Brigades (Enlarge)

The SFAB deployment model prioritizes persistent presence and geographical reach within each GCC. SFABs divide into three task forces, each of which takes turns rotating into the AoR for six months, maintaining the SFAB’s persistent presence.20 Unlike the first SFAB deployment in 2018, where all advisors concentrated in Afghanistan, small advisor teams now spread out to various partner nations within the region.21 Often, advisors deploy to remote locations with minimal oversight, underscoring the importance of selecting advisors whom SFAC can trust with this autonomy. SFAC has about 800–1,000 advisors deployed daily and, as of 2022, has had engagements with 54 countries.22

Because of the geographical diversity of the SFABs, there is no “typical” deployment. SFABs tailor their missions to host nation and GCC requirements and thus vary between and within regions. In South America, for example, 1st SFAB has trained counternarcotics forces.23 In Africa, 2nd SFAB trained Senegalese forces for their United Nations peacekeeping mission in Mali, while an engineering team trained forces in Ghana to plan and design a base camp.24 Missions can also be more traditional, such as 3rd SFAB’s focus on training counterterrorism forces,25 4th SFAB training Georgian forces on new weapon systems,26 or 5th SFAB participating in multinational exercises throughout the Indo-Pacific.27

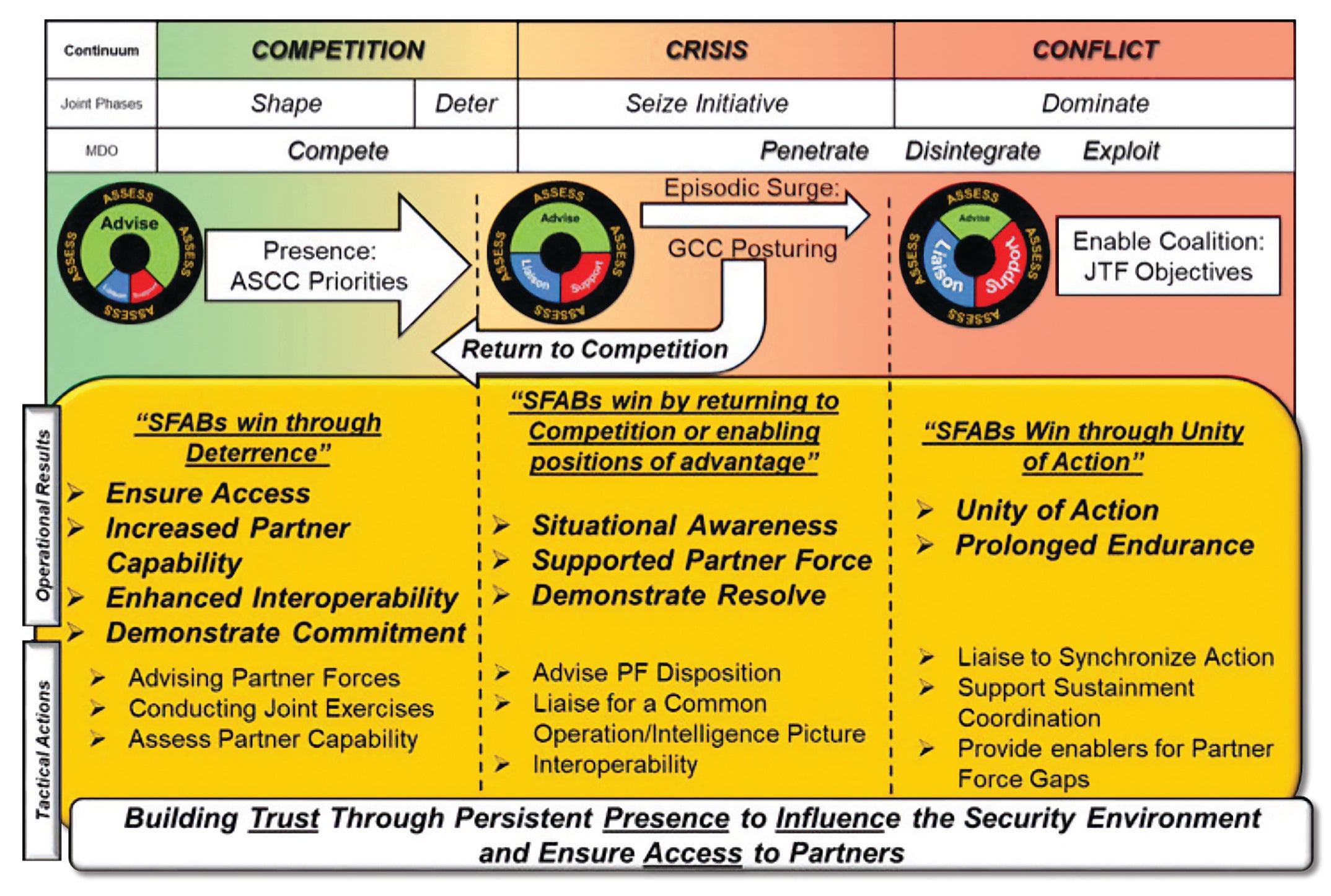

Figure 2: SFAB Functions Across the Conflict Spectrum28 (Enlarge)

Figure 2: SFAB Functions Across the Conflict Spectrum28 (Enlarge)

SFAB Value

SFABs operate across the conflict spectrum (see Figure 2). In competition, SFABs contribute to deterrence through a persistent presence in the contact layer of strategic competitors while building partner interoperability and situational awareness for joint and coalition forces. Competing enables prevailing in conflict by providing the joint force positional advantages and interoperability for multinational operations. SFAB regional alignment tailors these contributions to each AoR’s specific operational environment, security challenges and partner capability.

Compared to previous SFA, SFABs preserve the Army’s warfighting readiness. With enormous demands for training Afghan and Iraqi forces, the Army utilized portions of conventional brigade combat teams (BCTs). Because SFA benefits from more experienced Soldiers serving as advisors, the Army typically assigned BCT leadership (senior NCOs and mid-level officers) to these roles, breaking them away from the BCT’s junior officers and enlisted ranks. With senior leaders gone, remaining Soldiers were limited to training at the individual and squad level, degrading unit readiness.29 While this system was tolerable in low-intensity conflicts, potential large-scale combat operations require training at higher echelons. Hence, the Army created the SFAB as a dedicated advisory formation to preserve BCT readiness.

Ironically, SFABs may even improve the Army’s tactical warfighting capability. SFAB advisors must not only be experts at skills vital to squad-level effectiveness, including marksmanship, communications and the military decisionmaking process, but must also be effective at imparting these skills to others. SFAB advisors gain unique experiences in complex environments that Soldiers in other conventional units may not have. Once advisors finish with an SFAB, nearly all return to conventional Army formations in leadership roles, where they can impart their skills and experiences to their new formations.30

Guyana Defense Force (GDF) personnel and Florida Army National Guard Soldiers with B/2-54th Security Force Assistance Brigade assess security tactics during a knowledge exchange at Base Camp Stephenson, Guyana, 22 March 2022. Guardsmen and GDF members collaborated on best practices regarding security and recovery scenarios, which gave servicemembers the opportunity to share their knowledge and experiences while building both individual and team skills (U.S. Army photo by Sergeant N.W. Huertas).

Guyana Defense Force (GDF) personnel and Florida Army National Guard Soldiers with B/2-54th Security Force Assistance Brigade assess security tactics during a knowledge exchange at Base Camp Stephenson, Guyana, 22 March 2022. Guardsmen and GDF members collaborated on best practices regarding security and recovery scenarios, which gave servicemembers the opportunity to share their knowledge and experiences while building both individual and team skills (U.S. Army photo by Sergeant N.W. Huertas).

SFABs are also critical to the Army’s modernization at the operational and strategic levels. At first glance, SFABs may appear unrelated to the MDTFs—multi-domain maneuver elements that synchronize long-range precision effects—such as electronic warfare, space, cyber and information—with long-range precision fires. In fact, SFABs and MDTFs, with their overlapping regional alignments, are synergistic.

SFABs are crucial to achieving the positional advantages within adversary antiaccess/area-denial networks that MDTFs rely on to create and exploit advantages.31 Some local partners may be apprehensive about basing more provocative MDTF capabilities, such as long-range fires, in their nations.32 Because SFABs contain fewer high-end capabilities than MDTFs, they may be a more attractive initial option for partnership with the U.S. military. SFABs can form trust between the United States and partner militaries and so set the foundation for future MDTF presence. SFABs also enhance MDTFs’ non-lethal effects. For example, a Multi-Domain Effects Battalion (MDEB) seeks to exploit cyber and information advantages during competition.33 The SFABs’ understanding of local politics, culture and security concerns can enhance the MDEB’s ability to identify and counter adversary disinformation campaigns with locally relevant messaging aimed at critical populations.

SFABs and SF: Conventional versus Unconventional SFA

This paper does not fully examine Army SF’s extensive contributions to the SFA mission, but an overview of SF’s role clarifies distinctions with SFABs.

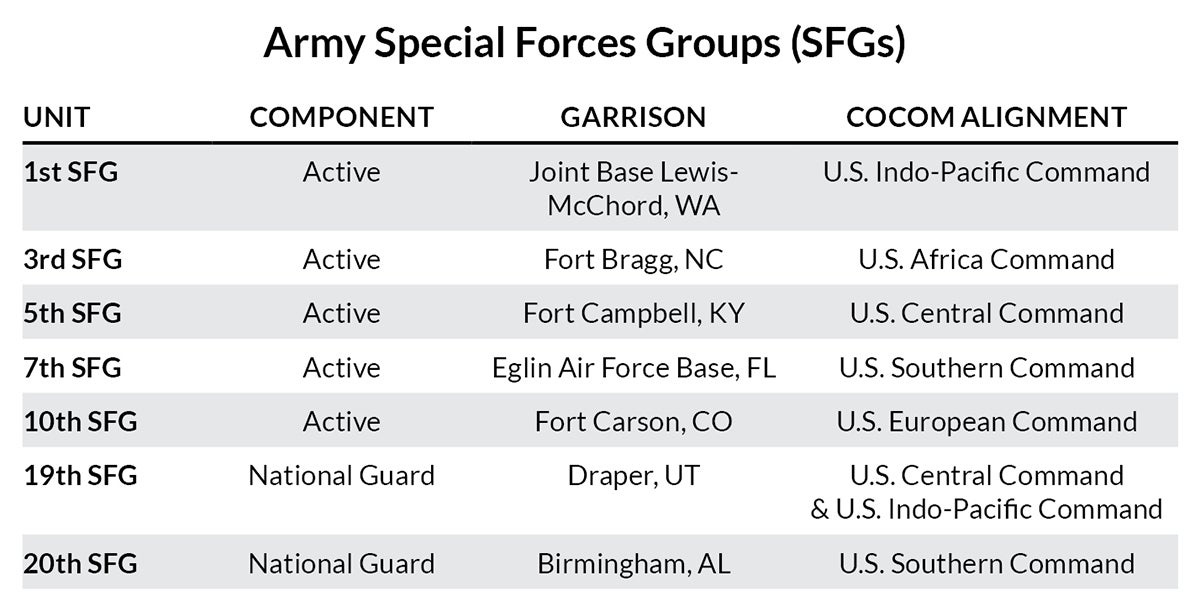

There are seven Special Forces Groups (SFGs)—five in the active component and two in the National Guard (see Table 2). SF’s foundation is the 12-man Operational Detachment–Alpha (ODA). A captain leads each ODA alongside a subordinate warrant officer and a senior enlisted advisor. The rest of the ODA comprises an intelligence sergeant and two Soldiers of each occupational specialty—weapons, communications, engineering and medical.34 It takes between 53 to 95 weeks for a Soldier to become an SF operator (depending on MOS).35 Candidates undergo extensive training, including in languages and cultural familiarization, allowing ODAs to operate covertly in denied environments, independently or alongside local partners, in a wide range of mission sets.

The primary distinction is that SFABs train foreign conventional forces while SF focuses primarily on foreign SOF and unconventional forces. SF evolved during the Global War on Terror (GWOT). Due to the premium placed on SOF to conduct counterterrorism, Army SF primarily trained Afghan and Iraqi SOF and accompanied them on raids. This development created the perception that Army SF exclusively trains foreign SOF and unconventional forces,36 which, although not doctrinally true, is often practical.

Table 2: Army Special Forces Groups (SFGs) (Enlarge)

Table 2: Army Special Forces Groups (SFGs) (Enlarge)

SFABs are better optimized to build conventional armies compared to SF. According to General McConville, “Special Forces is very good at training tactical-type units. . . . But SFABs build a professional military force, which is different. How do you do logistics? How do you maintain vehicles? How do you build a professional military that will provide security?”37 The disintegration of Afghan forces in 2021, largely due to ineffective logistics,38 captured this point.

Additionally, because a captain leads an ODA, they may not have the command experience to build conventional armies at the right echelon. As General McConville put it, “That captain has never been a battalion commander, never a brigade commander and maybe never even a company commander. . . . The SFAB is going to have a forward battalion commander that has run a battalion. . . . That’s how you professionalize these armies.”39

The second significant distinction is the purpose of SF and SFAB employment. According to an officer with command experience in both SF and SFABs, SF advising prioritizes “direct adversary-based outcomes” while SFABs focus on “partner-based outcomes with a more indirect effect on adversaries.”40 This is sensible, given SF’s doctrinal roles outside advising, including direct action, unconventional warfare and special reconnaissance, prioritizing effects on an adversary utilizing local forces. SF also maintains much more flexibility, conducting a wide range of operations as the mission dictates, supported by organic sustainment and mission command elements. Contrarily, SFABs have a singular, partner-oriented mission and rely on the Theater Army Service Component Command.41

In reality, SFABs complement SF by relieving SFA demands. Given the nature of operations, Army SF faced unprecedented deployment pressures during the GWOT.42 With growing global requirements for U.S. SFA, these demands are likely to remain high, despite the end of combat operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. SFABs can fill a gap by reducing pressures on Green Berets, particularly in cases where well-trained and experienced conventional Army NCOs can produce similar training outcomes, thereby freeing up SF for the missions that only they can conduct.

State Partnership Program (SPP)

While the contributions of SF and SFABs have received significant attention, SPP is more inconspicuous. According to the National Guard, SPP is a “Joint Department of Defense (DoD) security cooperation program managed by the National Guard Bureau, executed by the GCCs and sourced by the National Guards (NG) of the U.S. States and territories.”43 The purpose of SPP is to partner state NG units (both Army and Air Force) with foreign militaries, security forces and disaster response organizations.

A member of the 169th Cyber Protection Team (CPT) and members of the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina conduct cyber adversarial exercises at the Private Henry Costin Readiness Center in Laurel, Maryland, on 29 June 2022. Beginning in August 2018, the 169th CPT has supported the military-to-military knowledge transfer and team-building efforts to the Armed Forces Bosnia and Herzegovina under the State Partnership Program (U.S. Army National Guard photo by Sergeant Tom Lamb).

A member of the 169th Cyber Protection Team (CPT) and members of the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina conduct cyber adversarial exercises at the Private Henry Costin Readiness Center in Laurel, Maryland, on 29 June 2022. Beginning in August 2018, the 169th CPT has supported the military-to-military knowledge transfer and team-building efforts to the Armed Forces Bosnia and Herzegovina under the State Partnership Program (U.S. Army National Guard photo by Sergeant Tom Lamb).

SPP Organization

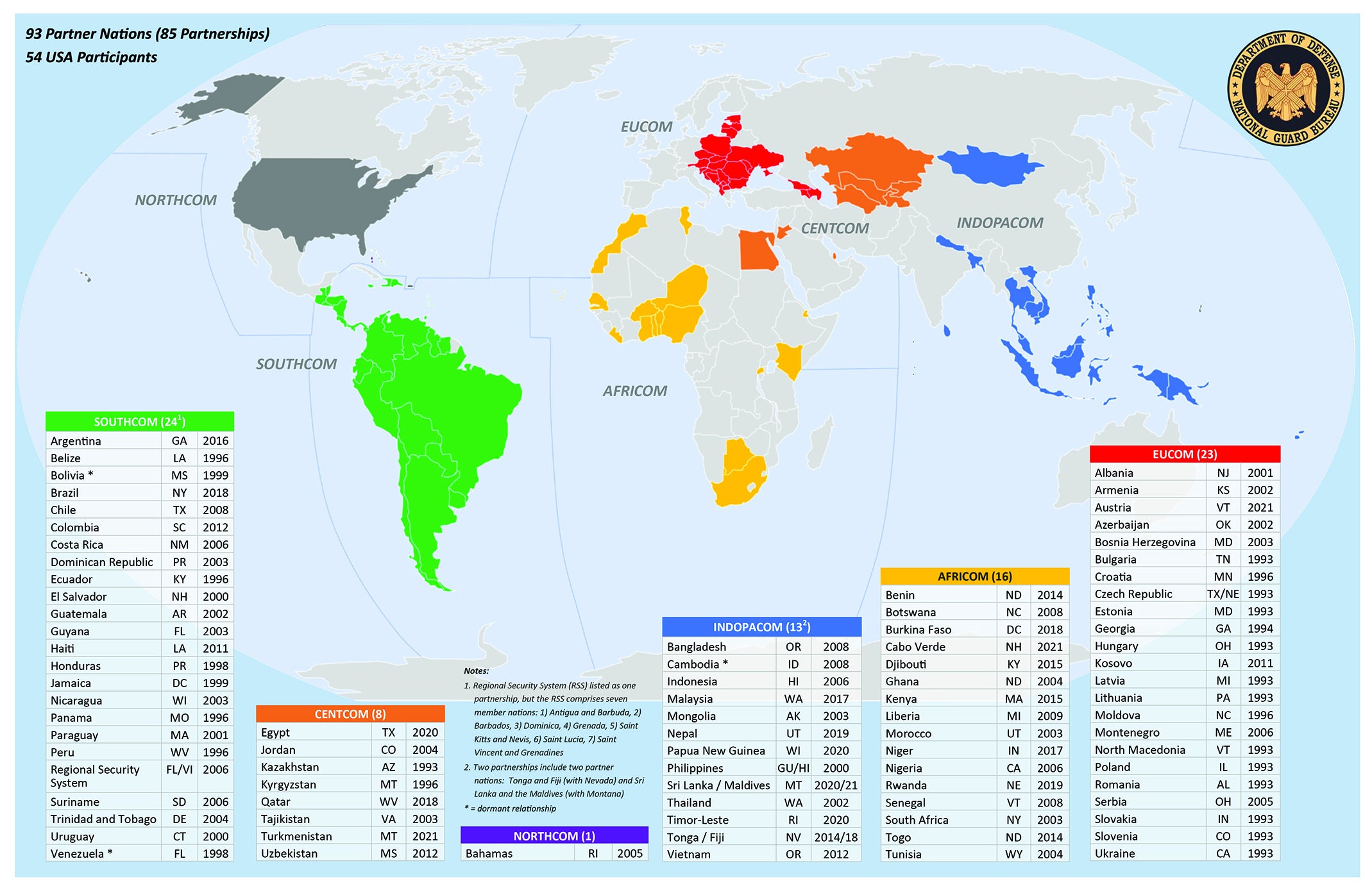

SPP began in 1993, first partnering with the three Baltic Republics. In less than 30 years, SPP has grown to 85 partnerships with 93 different nations (approximately 45 percent of all countries) across every region (see Figure 3). All 54 U.S. states and territories participate, allowing SPP to conduct over 1,000 events yearly, and the program grows by an average of two partnerships per year.44 Due to the number of partnerships, differences between U.S. state NGs and the variety of partner requirements, there is no standardized SPP deployment structure like that of an SFAB or SF. SPP tailors programs to GCC and partner requirements, including senior leader engagements, familiarization visits, training and exercises, subject matter exchanges and co-deployments. Focus areas include infantry tactics, counterterrorism, engineering, medicine, cyber, disaster response and leader development.

Figure 3: State Partnership Program Map45 (Enlarge)

Figure 3: State Partnership Program Map45 (Enlarge)

SPP Value

SPP’s most important quality is its potential to cultivate long-term interpersonal relationships with partner forces. While SF and SFABs benefit from a more persistent presence than SPP, they have a frequent officer and enlisted turnover rate.46 Contrarily, because many Guardsmen remain in one state for their entire service, they can cultivate years- or even decades-long relationships with partner Soldiers as they rise through the ranks.47 These long-term interactions facilitate a deep understanding of security concerns, capability gaps and opportunities for engagement.

As an NG program, SPP is highly cost-effective. Though SPP partners with nearly 45 percent of the countries in the world, its annual budget is only $40 million.48 Army Guardsmen attend the same Basic Combat Training as active-duty Soldiers, but they cost the Army less annually because they are part-time, train less frequently and do not require other living expenses. Similarly, SPP deployments are typically shorter-term; consequently, they do not require the same investment as SF or SFABs. Though there may be a tradeoff in capability associated with this lower cost, the outcomes of these partnerships are highly beneficial.

Despite this cost-effectiveness, SPP can provide unique skill sets. Given the National Guard’s predominant domestic role compared to the active component—for example, natural disaster response—SPP is particularly valuable for building partners’ domestic resilience. Likewise, Guardsmen can work in the private sector, often at the forefront of innovation with relevant military applications. Guardsmen may have civilian expertise in cyber, logistics, information technology, or healthcare that they can contribute to their partner force. The 19th and 20th Special Forces Groups are also within the Army National Guard and, therefore, can contribute their skills to SPP partners.

Additionally, SPP’s scale is conducive to partnering with a national military. Compared to regionally aligned SFABs and SFGs, a better ratio exists between the number of troops in a partner’s army and the number of Guardsmen a state provides. The Army National Guard’s (ARNG) endstrength as of March 2022 was 325,393 Soldiers.49 Texas, the state with the largest ARNG, has over 19,000 Soldiers;50 an SFAB has only 800. U.S. geographical diversity offers opportunities to partner states and nations with similar operational environments,51 enhancing the value of training. Moreover, if a country requires a capability that its NG partner does not possess, it can link with an alternative state NG that does possess the required capability.

Finally, SPP has significant potential to achieve soft power outcomes outside the military. Because Guardsmen are “citizen Soldiers” with extensive roots in the civilian world, there is a greater likelihood that these partnerships transcend into whole-of-society relationships. Partner states and nations conduct civilian leader engagements, which can include industry and create commercial opportunities.52 Likewise, SPP partnerships may set the foundation for academic collaboration, such as the university exchange program between Iowa and Kosovo.53 SPP military outcomes may be secondary to the broader networks formed, particularly in strategic competition.

SFABs, SF and SPP, with their complementary roles, provide combatant commanders a suite of SFA capabilities across the spectrum of competition, crisis and conflict. With this triad, the Army possesses a regionally tailorable capacity to train conventional and unconventional forces while promoting governmental and societal engagement. Still, the Army, Pentagon and Congress can take steps to improve the impact of advisory missions.

Recommendations

Army

Recommendation 1: Ensure close coordination and alignment between SFABs and MDTFs. Successful maneuvering in competition is the foundation for MDTF operations in crisis and conflict; SFABs are integral to the necessary access and influence that MDTFs exploit.

Recommendation 2: Prioritize fully manning SFABs because of their importance in competition. Senior NCOs and mid-level officers are critical to ensuring that unit culture remains conducive to representing the U.S. military in remote locations with little oversight.

Recommendation 3: Pursue opportunities to incorporate the synthetic training environment (STE) into SFA. Though there is no replacement for interpersonal advising missions, and not all partners will have the necessary technological capacity, the STE can supplement existing relationships to promote persistent presence. If necessary, it can serve as an alternative where the deployment of U.S. advisors is politically sensitive.

Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)

Recommendation 1: Synchronize integration of partner force capability assessments across the tactical and strategic levels of analysis. For example, a disconnect was evident between tactical assessments of the Afghan National Army and the feasibility of these units resisting the Taliban. Learning from this misalignment may ensure that political leaders understand partner force capability in future SFA missions.

Recommendation 2: Leverage the Army’s landpower network to expand joint force exercises with coalition partners.

Recommendation 3: Analyze the impact of Army SFA in Ukraine to generate lessons learned that may apply to the defense of Taiwan.

Congress

Recommendation 1: Adequately fund SFABs and SFGs to enable a globally expansive, persistent SFA network. Should the Army see the need and have the necessary endstrength, consider funding a second SFAB for the Indo-Pacific, as this region’s importance and size would benefit from a more prominent advisor presence.

Recommendation 2: Ensure consistent, stable funding for SPP. This program’s outsized influence for the United States is significantly disproportionate to its dollar investment.

Recommendation 3: Sustain congressional support for U.S. training and advising of the Ukrainian military and apply these lessons to Taiwan. Robust U.S. training and support for Ukraine sends a strong signal to adversaries of the efficacy of U.S. commitments to its partners. China has taken notice and will likely consider these factors in operational planning against Taiwan.

Conclusion

The Army’s SFA triad is critical to its modernization for strategic competition and MDO. SFABs, SF and SPP maximize the economy of force by strengthening deterrence, lowering the burden on American forces and promoting U.S. global influence. With the international order under strain, Washington must proactively grow its unmatched network of partners. This coalition of like-minded nations, united by shared values, is invaluable in the era of strategic competition.

★ ★ ★ ★

Charles McEnany is a National Security Analyst at the Association of the United States Army. He holds an MA in Security Policy Studies from George Washington University.

- Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, November 2021), 192.

- Aaron Mehta, “DoD needs 3-5 percent annual growth through 2023, top officials say,” Defense News, 13 June 2017.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 1 June 2022, 1.

- Sophia Ankel, “These are the 31 countries that don’t have a military,” Business Insider, 11 October 2019.

- Center for Security Policy, Stopping A Taiwan Invasion: Findings & Recommendations from The Center for Security Policy Panel of Experts (Washington, DC: Center for Security Policy, 25 April 2022), 68.

- Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-07.1, Security Force Assistance (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, May 2009, 1-1).

- Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, “Secretary of Defense Remarks at the 40th International Institute for Strategic Studies Fullerton Lecture,” DoD News, 27 July 2021.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 1.

- Michael Lee, “The U.S. Army’s Green Berets quietly helped tilt the battlefield a little bit more toward Ukraine,” Fox News, 24 March 2022.

- Jim Garamone, “Ukraine-California ties show worth of National Guard program,” DoD News, 21 March 2022.

- James Mattis, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America, January 2018, 8.

- DoD, Fact Sheet: 2022 National Defense Strategy, 28 March 2022, 2.

- Thomas Brading, “Strength in Indo-Pacific relies on partnerships, says Army chief of staff,” Army News Service, 21 May 2021.

- Todd South, “Advising everywhere: Army SFABs go smaller, farther,” Army Times, 14 February 2022.

- U.S. Army Security Force Assistance Command (SFAC), Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 2022, 26–27.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 1.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 2.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 2.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 1.

- John Amble and Colonel Curt Taylor, “Security Force Assistance in an Era of Great Power Competition,” Modern War Institute, podcast, 8 July 2020.

- South, “Advising everywhere: Army SFABs go smaller, farther.”

- South, “Advising everywhere: Army SFABs go smaller, farther.”

- SFAC, Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 26–27.

- SFAC, Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 14–15.

- SFAC, Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 16–17.

- SFAC, Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 18–19.

- SFAC, Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 20–21.

- Thomas Shandy, “SFAC: What Does Winning Look Like in the Continuum of Conflict?” Security Force Assistance Command, 29 September 2020.

- Congressional Research Service, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” 1.

- SFAC, Security Force Assistance Command Factbook, 9.

- Charles McEnany, Multi-Domain Task Forces: A Glimpse at the Army of 2035, Association of the United States Army, Spotlight 22-2, March 2022.

- Lieutenant General Stephen Lanza, USA, Ret., and Colonel Daniel S. Roper, USA, Ret., Fires for Effects: 10 Questions about Army Long-Range Precision Fires in the Joint Fight, Association of the United States Army, Spotlight 21-1, August 2021.

- McEnany, Multi-Domain Task Forces: A Glimpse at the Army of 2035, 4.

- “Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha (SFOD A)," American Special Ops.

- “US Army Special Forces ‘Green Berets’| The Complete Guide,” SOFREP, 19 June 2021.

- Tim Ball, “Replaced? Security Force Assistance Brigades vs. Special Forces,” War on the Rocks, 23 February 2017.

- South, “Advising everywhere: Army SFABs go smaller, farther.”

- The reasons for the disintegration of the Afghan National Army are myriad and not the purpose of this paper. For a detailed explanation, see Jonathan Schroden, “Who is to Blame for the Collapse of Afghanistan’s Security Forces?” War on the Rocks, 24 May 2022.

- Kyle Rempfer, “Army advisers in Africa following spike in combat,” Army Times, 24 March 2020.

- Major Christopher R. Thielenhaus, “Special Forces vs SFAB: It’s Not a Competition,” Infantry 110, no. 2 (Summer 2021): 21.

- Thielenhaus, “Special Forces vs SFAB: It’s Not a Competition,” 21.

- Stavros Atlamazoglou, “20 years of fighting terrorism took a heavy toll but has helped prepare for a bigger fight, US special operators say,” Business Insider, 14 October 2021.

- U.S. Department of Defense National Guard Bureau, The State Partnership Program, January 2022, 2.

- U.S. Department of Defense National Guard Bureau, The State Partnership Program, 3.

- U.S. Department of Defense National Guard Bureau, The State Partnership Program, 4.

- General Daniel R. Hokanson, “The National Guard’s State Partnership Program and Its Role in the National Defense Strategy,” The Heritage Foundation, 9 May 2022, video, 13:20.

- Hokanson, “The National Guard’s State Partnership Program,” 12:45.

- U.S. Department of Defense National Guard Bureau, National Guard State Partnership Program Fact Sheet.

- Defense Manpower Data Center, Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country, March 2022.

- Defense Manpower Data Center, Military and Civilian Personnel.

- Hokanson, “The National Guard’s State Partnership Program,” 14:04.

- U.S. Department of Defense National Guard Bureau, The State Partnership Program, 7.

- Claire Quigle, “Transforming Education in Kosovo,” University of Iowa College of Education, 1 December 2020.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.